Earlier this month a young biracial woman denounced her white father at his funeral. In her speech she said of her father:

You’ll never be what you could have been, but only what you are. And what you are is a racist, misogynistic, xenophobic, Trump-loving, cis, straight white man. That is all you will ever be to me.

There are two striking things about this. First, it demonstrates clearly the changed understanding of the virtue of justice. In the ancient world, justice meant giving someone their due. This meant giving due respect to those entities who gave us our existence, including God, our parents and our larger national family. "Honour your father and your mother" as it says in the Bible. In Ancient Rome, this was considered to be an aspect of the natural order to be upheld through the virtue of "pietas", defined by the Encylopaedia Britannica as "a respectful and faithful attachment to gods, country, and relatives, especially parents".

Justice in our own times has mostly lost this ancient meaning. It is now focused on notions of social equality. You can see this in the daughter's speech: she castigates her father for his transgression of modern ideas of equality, i.e. for being racist and sexist and for belonging to supposedly privileged groups (white, male, cisgendered etc.)

In her mind, she is fighting to make the world a better and more just place. To more ancient minds, she is acting unjustly in disrespecting her own father at his funeral. A key question here is why this transition in the meaning of justice has taken place. I will give a possible explanation shortly, but it will help first to look at another striking aspect of the speech, namely what it demonstrates about social class.

The father in question is Donald Foss. He was worth $2 billion at the time of his death and so was part of an upper class elite. His daughter was raised in a position of immense class privilege, living in mansions and attending elite private schools.

And yet his daughter, with a furious energy, chooses to present herself as being at the bottom of the social hierarchy and as being a victim of privileged forces, such as white, male, "cisgendered" men like her father.

Again, there has been a transition here in how the upper class justifies its privileged social position. In the past, the elite would signal its status through refinement (of manners, of speech, of taste); through displays of wealth (homes, clothing, banquets); and through cultivating knowledge and an appreciation of the fine arts. There was also the important concept of noblesse oblige, meaning that if you were noble in status you should act nobly in character ("Whoever claims to be noble must conduct himself nobly"). Noblesse oblige was also understood to mean that those in a privileged social position had a duty toward those less privileged - so this concept connected the upper classes in a positive way toward those of other social classes.

The older justification of wealth and privilege barely exists today. It is true that modern day billionaires do sometimes commit to philanthropic causes, although these are often international efforts to promote some form of "identity equality". What is increasingly common, though, is for upper class people to seize upon identity politics to claim to be suffering from some form of oppression, i.e. to present themselves as lacking privilege rather than enjoying it.

Which brings me to my theory of why this change has taken place. If we consider the world picture that existed in the ancient world, and compare it to that of modern times, one significant difference is the loss of the idea of a great chain of being. There were two key aspects of this chain of being. First, it was hierarchical. Those further up the ladder had more elevated attributes. Second, every creature in the chain was necessary to hold it together and so, in this sense, each was a vital link.

It has to be remembered that this chain of being was thought of, in concrete terms, as representing the way that the cosmos was structured. In other words, reality was understood through this idea of a chain of being.

One of the consequences of understanding the world this way, is that there was both an "above" and a "below" when it came to man's position in the cosmos. Above man were the angelic beings and God, below man were the animals and the inanimate forms of creation. There was a vertical realm of existence within which man could look upwards, but also could feel set above and therefore dignified in his position.

What I would like to conjecture is this: that if your world picture included the great chain of being, then it was possible to believe that if you were higher up the social ladder that you represented something higher in the scale of being. If so, the major distinction between the social classes, of nobility and commoner, would be a relatively profound one. It would not just rest on money or power, but would signify also an "ontological" difference, i.e. of being formed in some higher way.

In the American Declaration of Independence there is a famous phrase that "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal". This is not obviously true. Men are clearly not equal in many respects. It is possible that the emphasis here is on men having equal rights. Perhaps, though, it is also a move away from the older view, in which the distinction between nobility and commoners really did suggest men being created unequally.

This elevated view of the nobility can be seen to have had both positive and negative consequences (sometimes intermixed). For instance, it makes sense in such a social situation for people to look up to and to seek to emulate the culture of the upper classes, since this culture will be thought of as being higher up a scale of existence. This is clearly preferable to the situation in our own times in which culture looks downwards, so that the middle-classes begin to ape behaviours once associated with bikies, sailors or "gangtas".

On the other hand, when you have an elevated upper class, the possibility emerges of people fawning to this social class. It's interesting in this regard that nineteenth century Australian culture strongly rejected this aspect of old world culture and replaced it with a more egalitarian "mateship" ethos (Australian soldiers in WWI had a reputation for not respecting officers as they were supposed to).

Again, if I am right here, and the nobility thought of themselves as being a breed apart, this would anchor their identity, in part anyway, on the possession of higher attributes of character that they would then have to live up to. Yes, it might justify snobbishness as well, but it softens the idea that class privilege is only about power or money. It provides a foundation for more positive ideals of what it means to be upper class.

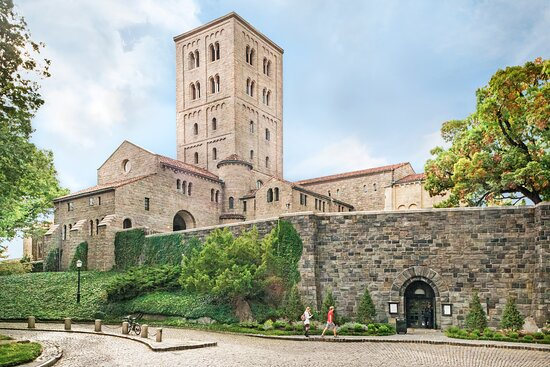

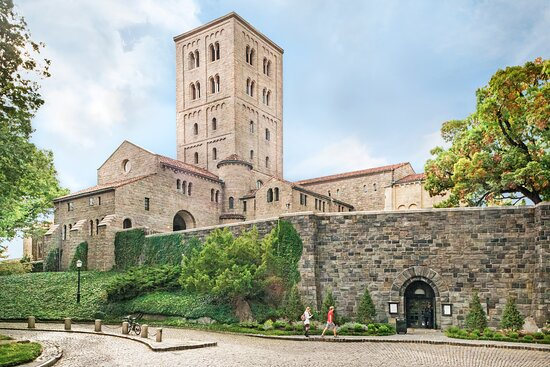

The older concept of the nobility still retained some influence in the modern period, at least until the early 1900s. For instance, if you look at the magnates of the American Gilded Age you find a mixture of modern sensibilities (e.g. technocracy), with some admiration for an aristocratic past. J.P. Morgan, for instance, built a beautiful library in a traditional style and collected older European manuscripts. The Vanderbilts married a daughter, Consuelo, to the Duke of Marlborough. John D. Rockefeller built a museum in a traditional European style in New York, The Cloisters, and purchased many medieval artworks for display.

|

The Cloisters, New York

|

|

The Morgan Library

|

If the secular order of the pre-modern West had a built in, inegalitarian social hierarchy, this was balanced to some degree by the clerical or religious order. I mean this not only in the sense that commoners could rise through the ranks of the church, and not even in the sense that the Christian belief that man was made in the image of God supported the dignity of the common man, but more fundamentally that the possession of the virtues most highly regarded within the religious life and the clerical orders did not depend on birth. Ascent within the clerical orders or the realm of religion was measured by faith, love, piety and sanctity, and these did not depend on birth (the New Testament, of course, emphasises that the poor are not disadvantaged in their spiritual fate).

In this way, the existence of a hierarchical social order was most likely of great benefit to the Church, as it made Christianity that order of life through which the common man could ascend or in which he stood on equal ground. This may help to explain the discontent when the Church hierarchy too closely mimicked that of the aristocracy, as it might have seemed at odds with the true function or role of the Church.

There were radical religious movements which rejected the idea of two orders, and which wanted to abolish the hierarchy within the social realm. They sometimes pointed out that in the prelapsarian state of man, in the Garden of Eden, there were no social classes. They were levellers of one sort or another. Looking back, they seem to have missed the symbiotic relationship between the secular and religious orders. What Christianity offered was made more compelling by the existence of a hierarchy within the social realm. To put this another way, there was an important space made available to Christianity, one in which Christianity was a necessary component of a working order of life, because of the existence of a hierarchical social realm.

Marx got it wrong in claiming that religion was the opiate of the masses. It was not anything like the bread and circuses of the Romans, nor the distractions of the modern era (Netflix, food courts etc.). Religion in Western civilisation undergirded the dignity of being for the common man - it was the order of life in which the common man held no inferior status of being.

So what do we make now of the great chain of being? I think the loss of this concept has, overall, been damaging. John Lennon boasted about the loss of an above and a below ("no hell below us, above us only sky") but this flattening of our metaphysical horizons has had mostly negative effects.

The great chain of being gave man a distinct place between the purely spiritual realms and the material. (This is, in my opinion, an accurate description of what man is made to be in this life: a creature who experiences, in a profound way, the confluence of the spiritual and the material.) The position of man spanned both realms, with space to be grounded within this material world but also then to reach into the spiritual - without which there is a disenchanting of the experience of life.

The loss of any above or below represents a hemming in of man's being. It is, perhaps, little wonder that so much emphasis was then put on an ideal of autonomy, in which it was thought that man could be less straitjacketed or caged through a freedom to self-define or self-create. This is reasserting some ontological space but more as a subjective expression of will rather than as an objective feature of existence.

What I would emphasise, however, is the effect of this metaphysical flattening on social class. We were clearly better off when the upper class set the tone, not only in manners or fashions, but by attempting to live as a more "noble" class ought to live. And we were better off when this upper class accepted the reality of privilege but compensated not through virtue signalling but by accepting responsibilities and duties to others of their own community.

It is not that the concept of a chain of being can, or should, be recreated exactly as it was in medieval times. We are clearly not, for instance, going to think of the physical cosmos in terms of such a chain as was once the case. We do, however, need to assert more than a horizontal dimension of existence - there is a vertical one as well, which if denied or obscured has damaging consequences.