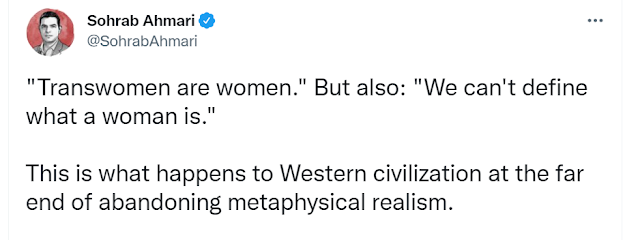

You can see here the logic of nominalism (that there are only individual instances of things) and a certain type of materialism (that we are just matter in motion) in undermining a "teleology" - a view that there are proper ends to human life that are discernible through reason.Sohrab Ahmari had a similar take on the Matt Walsh discussion:

Friday, January 21, 2022

Can modern society define what a woman is?

Friday, January 14, 2022

The rights place

I am currently reading The Unintended Reformation by Brad S. Gregory. I am learning much from the book about the history of ideas - it is worth reading for this alone.

Gregory's most basic argument (I hope I do it justice in this summary) is that an unintended consequence of the Reformation was a proliferation of truth claims and that various attempts to finds ways to adjudicate between these failed. This contributed to the period of political instability and warfare which devastated parts of Europe in the later 1500s and 1600s. This then encouraged a shift from an ethics of the good to one of rights. For a period of time a shared religious culture was able to provide an ethics of the good now missing at the formal, public level, but in the long run the effect was to subjectivise morality, so that the good was whatever I subjectively held it to be.

In Gregory's own words (p.226):

In an attempt to address the unintended problems derived from doctrinal disagreements in the Reformation era, Christian contestation about the good was eventually contained by the sovereign liberal state through individual rights. The political protection of rights has in turn unintentionally fostered the subjectivization of morality by legalizing the self-determined good as a matter of preference.

One of Gregory's many arguments is that the notion of rights was based on a concept of natural law, which made sense within the traditional understanding that man was made in God's image and that the natural world was God's creation. From this could be derived a view that man had been created in certain ways and for certain purposes that should not be violated - hence "rights".

However, when this traditional understanding waned, and was replaced with metaphysical naturalism (i.e. that there are only natural, material processes at work in the universe), then it becomes difficult to view rights as anything other than mere assertions. Gregory makes an interesting point about the incoherence involved in suggesting that moral actions are merely subjective preferences whilst violations of rights are inherently wrong (pp.225-226)

It is not uncommon to hear people insist on the constructed arbitrariness of moral values and yet denounce certain human actions as wrong because they violate human rights. That such a self-contradictory absurdity seems to be widespread and tends to escape the notice of its protagonists suggests both that it is deeply rooted and that it fulfils an important function...

The incoherence of such a pervasive sensibility - moral values are arbitrary but some actions are wrong - derives from unawareness of the historical genealogy of two desires that are contradictorily combined. The first seeks to maximise individual autonomy to determine the goods according to one's preferences (hence the advocacy for arbitrariness). But the second endeavours to uphold human rights as a safeguard against the horrific things human beings can do to one another depending on their preferences (hence the insistence on non-arbitrariness). The first desire is the long-term product of a rejection of teleological virtue ethics, the second a residue of the belief that human beings are created in God's image and likeness. Their combination depends for its appeal on a skepticism that goes only so far but no further. One needs to get rid of a God who acts in history, who makes moral demands and renders eternal judgements consonant with teleological and divinely created human nature. Otherwise human beings would no longer be the neo-Protagorean measure of all things, and the ideologically foundational modern commitment to the autonomous, unencumbered self would be threatened. But one equally cannot permit human actions that are consistent with the scientific finding that human being are nothing more than biological matter-energy. Otherwise human being would be ultimately no different from amoebae or algae....and one could act accordingly depending on one's preferences and desires. So souls must go, but rights must stay; skepticism must be embraced with a carefully calibrated and catechetically inculturated arbitrariness. It must be frozen where it unstably stood after the Enlightenment's supposed supersession of the Reformation era in the late eighteenth century: in just the rights place.

Gregory presses an argument in the book that what has been lost is an ethics of the good practised within a moral community. I thought this when I was still in my twenties, i.e. that a community has to be willing to articulate its vision of the good and to uphold it (reasonably) as a moral standard or norm. If it fails to do so (for instance, in the belief that it is not possible to discern such a good, or to come to a shared understanding of it), then there will be a lowering of the moral understanding within that community.