I am reading The Invention of Autonomy by J.B. Schneewind. I reached chapter five which is on Thomas Hobbes and, predictably, only read a couple of pages before becoming enraged and wanting to fling the book at a wall. This happens every time I read something on Hobbes - he is the person in world history I revile the most.

Interestingly, some of his contemporaries had the same reaction. For instance, in 1676 a German by the name of Samuel Rachel wrote: "We will give the last place to Thomas Hobbes for filth falls on the hindmost...Never...have I lighted on any writer who has put before the world views more foolish or more foul." Schneewind goes on to note that "Hobbes's theories...aroused lasting hatred and fear in some of the strongest thinkers of the time."

Why my visceral disgust? I think it is because Hobbes is incompatible with the best of the Western mind and soul. His ideas make impossible a distinction between what is noble and elevated and what is base and common. His ideas undermine the traditional concept of the good, the beautiful and the true. His ideas deny the affinities which naturally tie together human communities. His ideas are incompatible with finding a common good for human communities based on virtue or on the ordering of the social, spiritual and biological nature of man.

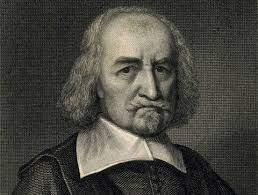

|

| Thomas Hobbes |

By the time I had finished the chapter I had calmed down. Schneewind does a decent job of explaining why Hobbes took the positions that he did. Hobbes was radically committed to scientism, nominalism, materialism, determinism and voluntarism and he was concerned, in an era marked by religious and civil war, to block any justifications for rebelling against the monarch.

It is a little difficult to condense Schneewind's arguments, so I'll focus on picking out a few of the more interesting parts.

First, Hobbes states directly that the point of moral philosophy is to avoid the calamity of civil war: "all such calamities...arise...chiefly from civil war...few in the world that have learned those duties which unite and keep men in peace...the knowledge of these rules is moral philosophy."

This is a poor foundation for moral philosophy but it shows how much the historical context matters.

Hobbes's materialism was radical. He thought that humans were just clusters of atoms. Sometimes the atoms move toward something and this is named desire. Sometimes they move away and this is named aversion. The radical consequence of seeing things this way is that the meaning of the term "good" changes. As Schneewind puts it:

When we are moved toward something, we call that toward which we are moved "good". Thus we do not desire something because we think it good. We think it good simply because the thought of it moves us to get it.

We are not moved toward the good; the good is a word we apply to whatever we are moved toward. As Schneewind puts it, "for Hobbes to call something good is only to say one wants it".

The endless pursuit of desire is, for Hobbes, the very thing that constitutes the motion of the self. Therefore, there can be no "final end" such as contentment in the knowledge of God, because "for Hobbes the absence of desire is the absence of motion, and that is, simply, death. Felicity lies rather in seeking and obtaining whatever we happen to want."

For Hobbes, our desires "stem from the interaction between our bodies and causal chains originating outside them, and they determine literally our every move". They are simply material effects that are part of the physical world. Therefore, Hobbes believes that desires cannot be ordered toward higher goods which might then form a common good around which communities might be harmoniously ordered.

This is not possible, first, because we will not find like-minded people, as the causal chains will act differently on people, creating desire in some and aversion in others. Second, there is no rational deity in this scheme of thought ordering the world toward harmony - the physical laws that act on people do so indifferently and without meaning. Finally, I would presume as well that Hobbes sees individual behaviour as being too rigidly determined by causal chains to allow for a process of rationally ordering goods.

What all this means is that Hobbes does not believe that you can find the civil peace, which he believes is the foundation of moral philosophy, via a common commitment to a set of goods (i.e. to a common good). He writes that there is no "common Rule of Good and Evill, to be taken from the nature of the objects themselves".

Schneewind proceeds to note Hobbes's famous belief that humans form communities not out of natural sociability or through love of other people but through self-interest. Here we get to specific pronouncements about the nature of man that form Hobbes's anthropology. Hobbes thinks we share a fear of death and a desire for glory. We have "an insatiable desire for security" (Schneewind) which makes us want to perpetually have superior power over everyone else, leading to a war of all against all. Our natural state is the most low trust condition you could imagine.

For Hobbes, this means that there are two laws of nature. First, to seek peace as a means to obtain security. Second, if this is not possible do what it takes to stay alive.

I want to pause here to reflect on the ramifications of this. Hobbes was committed to scientism in the sense of believing that a moral theory had to have a kind of mathematical certainty. He was not alone in this commitment; his chief English detractor, Richard Cumberland, felt obliged to respond to Hobbes via a scientistic approach to morality as well (there had been a strain of scepticism which denied that we can know anything with certainty which was one reason why some were pushed toward scientism).

You can see where this leads. You end up with some very basic foundational propositions. Man here is almost abstracted out of existence. All that Hobbes can say about man's nature is that he wants to live and that he wants power and glory. Hobbes does later claim that you can build a superstructure of beliefs about virtues and vices on the basis of his "natural laws", but it is still ultimately motivated only by the desire for self-preservation.

In the more traditional view, man as a creature has a distinct nature that a person will seek to develop to its higher purposes and ends in order to fulfil his or her own being. There are, for instance, qualities of manhood that a man will rightly seek to embody because they are an "essential" aspect of his nature, through which he completes or perfects his being in the world, and which represent a higher good that he aspires to embody. What this traditional view requires is not one or two "mathematical" foundational propositions, but an insightful description of what constitutes a masculine ideal for men to seek to live by - and this will be relatively complex, as it will bring together the physical, social and spiritual elements of a man's being and will also include the distinct roles of men within the family and society.

This makes little sense within Hobbes's world picture, as for him there are no objects that are inherently good, as something is made good simply by virtue of us wanting it. Hobbes's view does, it must be admitted, fit well within a consumer society based on the pursuit of individual choice in the market - perhaps this is part of what gives me the unsettling sense that we are living excessively through Hobbesian values in the modern world.

(I'll finish reporting on Schneewind's account of Hobbes in my next post.)

It sounds like Hobbes perfectly described NPCs because he was one. It is an unavoidable conclusion that some are empty shells with no soul and this is where atheists come from. And demons enter those shells. Hence we got a Hobbes, and the modern SJWs who are incarnations of the devil just like Hobbes. His voews asstated by you soubd very similar to modern buddhists, those soul denying NPCs...they must be being honest about their own lack of a soul.

ReplyDeleteGreat analysis. Yes one’s conception of Man will shape the way we view society. Whilst science is a powerful tool, scientism, it poses a reductionist view of Man stripping him of his nature and purpose thereby resulting in a very pessimistic and Machiavellian view of the social “order”. Tom

ReplyDeleteExactly!

DeleteThe arguments of Hobbes here strike me as an example of the wholelistic nature of truth, as opposed to a empirical set of facts alone. Its why truth is such a hard thing to truly hold.

ReplyDelete(And its why people can so easily argue past each other, holding to correct facts which the other side ignores, which allows both sides to be genuinely convinced of their correctness and the errors/ignorance of the other side)

For example, a lot of his individual statements strike me as true in a given situation.... we do call that which we desire the 'good', regardless of whether it actually IS. WE do this alot, especially as children, but it never stops. The whole point of wisdom, and transcedence, is to know the difference and escape the compulsion. Some of our desires do stem from bodily interactions, as a falling glucose blood level stimulates hunger. Pain triggers reflex avoidance.

Different people, whether by genetics or choice, will respond different to 'causal chains' and hence community is not an automatic or inevitable development from just ANY set of people. And while humans Do have a great need for security, and a drive for power to secure it, its only one of several needs. Yes we do fear death, but why does that determine only one course of action?

Further, the whole issue with any of these needs is not just their satisfaction, but their proper ordering and use in obtaining the actual good. Hobbes must know THAT?

To my thinking, this is even today the difference between truth and ideology. An ideology takes only some PART of what is true, and elevates it to the exclusion of all other parts of truth, and thus its manifestation in reality. That part, without the whole, is often right!!

I always think about truth as being what IS, what WILL be, and what COULD be.

So scientism, 'science' looks at what is, and in a given set of circumstances what WILL be (ie if A then B). But ideology cuts off even the option that there are other alternatives. Just my observations!