One of the worst features of our culture is misandry. The hostility toward men has become so open that it is beginning to draw criticism - just this week I have read two articles in the media focusing on this problem.

The first was written by Bel Mooney. She describes herself as a 60s feminist, but nonetheless is "disturbed" by the "wave of man-hating pervading our TV screens". She mentions several TV shows as evidence, but focuses particularly on Maid which she experienced as "deeply depressing" because every single man depicted in the show is "horrible".

|

| Maid - misandrist TV |

Bel Mooney believes that "we do not help women by demonising all men". However, when she suggested on Facebook that not all men were evil, she met with opposition. One woman told her that "You have to accept that men as a group really are s***".

Mary Wakefield also watched Maid and was similarly struck by its misandry:

I have Netflix, and in particular the series Maid, to thank for the startling discovery of how easy it is to slide into a form of man-hating — not a righteous feminist rage, but a sort of dopey, palliative, unthinking misandry.

She writes about the series that,

The distinctive thing about it is that every male character is an absolute horror. I mean: every single one.She admits that she was initially influenced by the anti-male message, before drawing back:

I looked back at any odd, unasked-for lunge in my past and saw it suddenly as part of a continuum of male sin that ends in wife-beating...My power trip lasted for 24 hours. At breakfast the following day, it occurred to me that I wasn’t remotely oppressed.

She continues:

I suspect it’s everywhere now, this almost invisible bigotry, streamed into our psyches via Netflix and Amazon Prime — what the French philosopher Élisabeth Badinter calls ‘the binary thinking of belligerent neofeminism’.

Where does this misandry come from? Something worth noting is the inversion of values. In traditional societies the role of men was to protect and to provide for women. It seems to me to be no coincidence that men are now characterised as having played the very opposite role. Instead of being protectors, it is asserted that men have historically been abusers of women. Instead of being providers, it is argued that men were exploiters of women (or even that they held women as property).

Inverting a truth is a way of rewriting an aspect of history or of reality. This process did not begin, on a mass scale, until Western society was wealthy enough for upper and middle class women to feel secure and less reliant on the traditionally masculine role.

When was the tipping point? Most likely when the industrial revolution really kicked in and considerably increased average incomes. This took place over several decades from about 1830 to 1860:

According to estimates by economist N. F. R. Crafts, British income per person (in 1970 U.S. dollars) rose from about $400 in 1760 to $430 in 1800, to $500 in 1830, and then jumped to $800 in 1860...Crafts’s estimates indicate slow growth lasting from 1760 to 1830 followed by higher growth beginning sometime between 1830 and 1860.

What was happening to feminism during this time? During the slow rise in income, there was no mass feminist movement. There were individual feminists like Mary Wollstonecraft, but the movement did not catch on. It was toward the end of the period of rapid income growth that feminism in the UK became an influential movement that began to be supported by the state. By the 1860s, the writer Eliza Linton was criticising the feminists of her era as "you of the emancipated who imitate while you profess to hate" and by the 1880s a Girton College girl was no longer looking to men much at all, having adopted the outlook that,

We are no longer mere parts - excrescences, so to speak, of a family...One may develop as an individual and independent unit.

What I am arguing here is that once society reaches a certain level of wealth, to the degree that upper and middle class women no longer fear material deprivation, that conditions exist for the traditionally masculine role to be attacked and subverted.

Modern metaphysics have also laid the groundwork for misandry. Traditionally, for instance, it was thought that the masculine had a real existence as a principle or essence that men could meaningfully embody and that potentially ennobled men as bearers of masculine virtue.

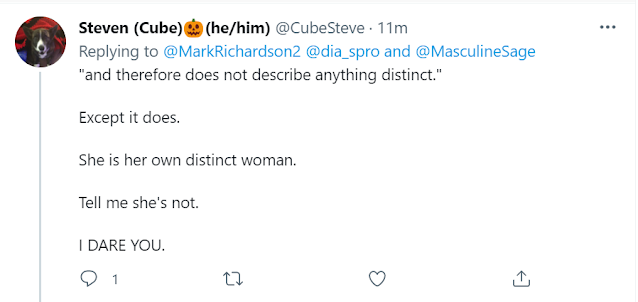

There do still exist women who think along these traditional lines and who associate the word "man" with positive characteristics which they admire:

However, there was a turn away from realism in philosophy centuries ago. What replaced it was nominalism, which emphasised instead the idea of there being only individual instances of things. Masculinity was no longer thought of as a transcendent good connected to virtue, but could now be rejected as being merely a social construct created for the purposes of empowering one group at the expense of another.

Modernist metaphysics is also grounded on a radically individualistic anthropology. Humans are understood to exist in a state of nature as atomised individuals pursuing their own selfish pleasures. They are only brought together into society through a social contract which has the aim of preventing violent conflict.

This anthropology undermines a deeper understanding of a common good in which we develop in relationship with others. Instead, as the Girton girl quoted above put it, it is assumed that we develop as "an individual and independent unit".

If so, we can be reckless in breaking faith with the opposite sex. We no longer need positive relationships between the sexes to fulfil the deeper aspects of our nature or to achieve our higher purposes in life.

What does fit within this modernist metaphysics is the pursuit of individual pleasure. And so, unsurprisingly, there is a shift in which relationships between men and women depend to an ever greater degree on sex itself - on the libido. This is not a basis for relationships that is likely to promote harmony and admiration. Eros alone does not provide for stable and secure relationships: the results over time will often be jaded feelings and a loss of trust, and this too can underlie the expression of misandry from women.

One of the consequences of liberal modernity having such an individualistic anthropology is that there is a loss of the group-focused moral foundations, such as loyalty, that are a part of more traditional societies. When people are focused on the good of the larger communities they belong to, and are loyal to them, it promotes a fellow feeling between the sexes. Men will express pride in "our women" as will women in "our men".

This concern for the larger community is one reason why Eliza Linton, who I quoted earlier, was so critical of the feminists of her time. She wrote of the movement in the 1870s that "it is still to me a pitiable mistake and a grave national disaster." Compare Eliza Linton's loyalty to her nation with the radical disloyalty of the English feminists described by Bel Mooney in her article on misandry. She attended an event to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of a charity for single mothers. The keynote speaker was not only hostile to men but, more specifically, to the men of her own tradition:

The party was held in the fine 18th-century surroundings of London’s Foundling Museum, set up by the great Thomas Coram who was horrified children should be abandoned by mothers too poor or shamed to care for them. The guest speaker was Jane Garvey, then a presenter of Woman’s Hour on Radio 4. She stood on the podium and began with the scornful jibe that there we were, in that room, ‘surrounded by portraits of fat, old, white men in bad wigs’.Again, there is not just a change of moral beliefs here but an inversion. It is no longer loyalty which is thought moral, but a mocking disloyalty.

You can see the tyrants, the invaders, the imperialists, in the fathers, the husbands, the stepfathers, the boyfriends, the grandfathers, and it's that study of tyranny in the home...that will take us to the point where we can secure change.It is only a short distance from this characterisation of men as tyrants to a more active hatred of men as a group. The misandry is not just an unfortunate quirk of a few unhappy women but rests on a set of metaphysical and political assumptions that are, for the time being, baked into our culture.