Earlier this summer eleven Australian women were murdered over a three week period. It led to a debate on social media about domestic violence and how it might be tackled.

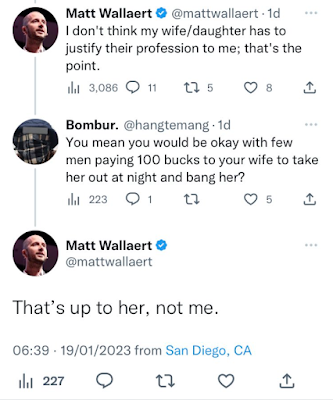

On one side of the debate were those who emphasised two things. First, that women are the victims of violence and men the perpetrators. Second, that the solution is for men to change, in particular, by becoming less repressed and by better expressing their emotions. For instance, one woman I engaged with ("Megwa") began by demanding that we "Fix the men". When I asked her what she meant by this, she replied "by taking down the patriarchal bs that inhibits teen boys from showing their emotions, oh sorry, fighting’s okay, but don’t cry."

a) The narrative

There is a strong tendency in these debates for the facts to be filtered to uphold a narrative of men as perpetrators and women as victims. This is despite the fact that men are considerably more likely than women to be the victims of violence (for instance, 70% of those murdered in Australia are men).

It is true that men are also more likely to be the perpetrators, though not to the extent that those who believe in the narrative imagine. For instance, my female colleagues guessed that when it comes to domestic violence that 95% of the perpetrators are men. The real figure is not nearly this high. The NSW Government provides up to date data on those brought to court by police on charges of domestic violence (i.e. physical assault). In the period from October 2021 to September 2022, there were 10,790 men proceeded against by NSW police and 4,531 women, giving a roughly 70/30 split.

If violence is caused by the socialisation of men, how then do you explain the 30% of domestic violence assaults that are perpetrated by women? There must be another explanation.

b) Men and emotions

There is a commonly held belief that problems in society are caused by boys being socialised to repress their emotions. If boys could be raised to be more girl-like in their emotions, the theory goes, then you would not have the pathologies of "toxic masculinity".

This idea is taken so seriously that there are organisations in Australia which go to schools and conduct group therapy sessions for the boys to guide them to release their feelings as a future model of masculinity.

Where does this belief come from? It is a survival of left Freudianism, one of those "accretions" within the larger political culture. I'm not as well versed in left Freudianism as I'd like to be, but my current understanding of it runs as follows. Freud himself thought that repression led to discontent within the individual but that it was necessary for civilisation. The left Freudians, in the mid twentieth century, took a different approach. They thought that it was not enough to have a political revolution to reform society - this had been tried in places like Russia but had led only to a new type of authoritarianism. To succeed, there had to be a psychological transformation of the individual and this would occur when the individual ceased to repress their instincts, feelings and emotions.

You get a sense of this left Freudianism in the claims that masculinity is toxic because it leads men towards dominance and power which is exerted in oppressing women through acts of violence and that the path forward is for men to not be socialised to repress their emotions and feelings. In other words, we have a left Freudian claim that an authoritarian personality type is being created via psychological repression.

This is often joined together with another accretion within our political culture, namely the leftist belief that there are power structures which have denied humans an Edenic existence of living in peace, harmony and equality. In this case, the power structure most usually targeted is the patriarchy, which is held responsible for encouraging boys to repress their feelings.

The American feminist Gloria Jean Watkins (commonly known by her pen name bell hooks) wrote a book titled The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity and Love (2004). In this work, she gives voice to these ideas about men. She complains that,

...masses of men have not even begun to look at the ways that patriarchy keeps them from knowing themselves, from being in touch with their feelings, from loving. To know love, men must be able to let go the will to dominate.

She adds:

...by supporting patriarchal culture that socializes men to deny feelings, we doom them to live in states of emotional numbness.

c) Criticisms

1. Lack of awareness

My first criticism of this common approach to ending male violence is that those who hold it aren't aware of where their ideas come from, i.e. that they are blindly following the accretions within modern political culture.

2. Rousseau

My second criticism is that there is a faulty assumption about human nature in this view, one that shares with Rousseau the idea that humans are good by nature but corrupted by society. This suggests that human nature is perfectible and that it is therefore reasonable to demand an end to male violence as an immediately achievable goal (some of those commenting on social media believe that it is within the power of men to stop other men from being violent). There is too little acknowledgement that human nature is flawed and that a complete eradication of violence is not a likely prospect, even in the most rationally ordered social settings.

3. Solipsism

Some of the women involved in the debate assume that if men are to have emotions they must be experienced and expressed in the same way as women - otherwise they do not exist. It is difficult to explain to these women that a man can have a rich inner life without being "emotional". Men are generally more able to be analytically detached from their feelings and to express them less overtly, but this does not mean that a man is incapable of love and other deeply felt inner states.

Despite claiming that men are emotionally numb in a patriarchy, Gloria Jean Watkins makes two telling admissions. First, she admits that men are able to love women for who they are, whereas women are more likely to care for men on the basis of a man's performative role:

We struggle then, in a patriarchal culture, all of us, to love men. We may care about males deeply. We may cherish our connections with the men in our lives. And we may desperately feel that we cannot live without their presence, their company. We can feel all these passions in the face of maleness and yet stand removed...Caring about men because of what they do for us is not the same as loving males for simply being. When we love maleness, we extend our love whether males are performing or not. Performance is different from simply being.

Second, she admits that she did not like her own partner opening up emotionally because it undermined her sense of his masculine strength:

When I was in my twenties, I would go to couples therapy, and my partner of more than ten years would explain how I asked him to talk about his feelings and when he did, I would freak out. He was right. It was hard for me to face that I did not want to hear about his feelings when they were painful or negative, that I did not want my image of the strong man truly challenged by learning of his weaknesses and vulnerabilities.

4. Raising boys

The idea that the key to raising boys is to encourage emotional vulnerability is not harmless, because it disrupts one important aspect in the raising of boys, namely the "make strong" ethos. It is normal and healthy for fathers to want to encourage physical and mental strength in their sons. This does not mean that boys or men should never seek help with problems, particularly if these are acute, but this is not the general mindset by which men seek to develop who they are as men.

5. Tackling violence

If the aim is to reduce the level of violence in society, it is important to understand what promotes it. The data suggests that violence is more likely to occur within a social underclass marked by drug and alcohol abuse, unemployment, homelessness and mental health issues. Anglicare Victoria has suggested that these factors are present in about 80% of cases of domestic violence. In cases of female homicide victims:

James and Carcach (1998) suggest that almost 85 per cent of victims, and a little over 90 per cent of offenders, belong to what can be described as an underclass in Australian society.

The aim should be, therefore, to do what can be done to limit the size of this underclass in if we wish to reduce the prevalence of violence. Asking ordinary men to cry more is not a targeted solution.

6. Repression & emotions

If the aim is to promote a healthier inner life for men, then the left Freudian idea of not repressing our feelings, instincts and urges is misguided. The better aim is to rationally order these feelings, instincts and urges both toward our own good and toward the common good. It is more in the failure to achieve this that our inner life is radically diminished and that we are cut off from sources of love and connectedness, i.e. that we become emotionally and spiritually damaged or broken.

If we truly want to help men live an emotionally rich life, then we should encourage earlier family formation; a more stable culture of family life; an opportunity to provide and protect for a family; a more secure experience of fatherhood; a reasonable work/life balance, including an opportunity to cultivate male friendships within male social settings; an opportunity for serious participation within a religious tradition; an active participation within a polis; and a culture which connects men to their family lineage and to their own ethny and culture.