This week there was a debate on social media about whether porn should be banned. I found the response of the libertarian right to be very interesting. They reacted vehemently against the idea of a ban as a matter of principle, claiming that those supporting it were "fascists" or supporters of theocracy and were acting against the ideals of the US as set out by the founding fathers.

The debate was therefore useful in highlighting some important philosophical differences on the right, particularly regarding the notion of a common good.

One person on the right advocating for restrictions on pornography is Matt Walsh. He attracted a lot of fire from libertarians for his stance. Walsh linked the debate to the issue of the common good in this tweet:

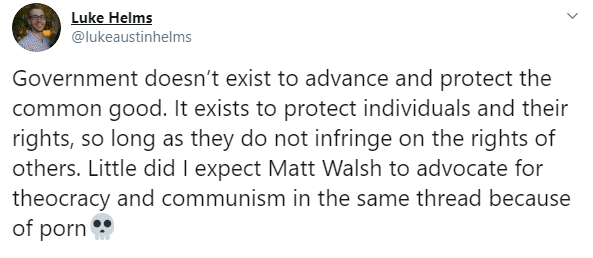

The libertarian response accusing Walsh of "theocracy" came soon after:

Back to Walsh:

Back to libertarians:

Once more to Walsh:

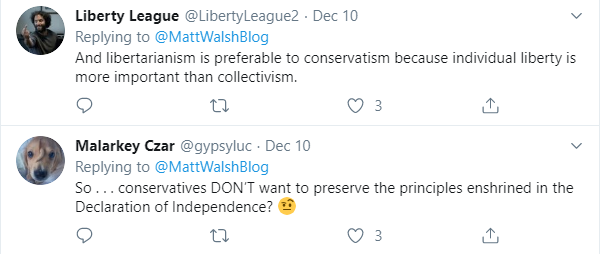

At this point libertarians stepped in to associate any notion of a common good with the sin of "collectivism" or with abandonment of American founding principles. For example:

One of the errors I think libertarians make is to set in opposition the notion of the individual good and the common good. In reality, the two are interconnected. I put it this way in a tweet of my own:

The mistake seems to go back all the way to Locke, from whom the notion of the "individual pursuit of happiness" derives. If my understanding is correct, Locke himself did not believe that individuals should simply "live how they deem fit". He thought they should pursue happiness, by which he meant that they should use their reason to avoid immediate gratification in favour of the higher pleasures associated with a life of self-disciplined virtue.

For this reason, modern day libertarians have drifted away from the mindset of the American founders, who emphasised the connection of virtue to liberty, and licence to the destruction of liberty, a point I will develop below.

Even so, the Lockean outlook has proven to be insufficient. Locke thought that we were born as blank slates, with no inborn nature, and no propensity to either good or evil, but that we were products of our experiences. He seems to have underestimated the fallen nature of man. Left to a purely individual pursuit of happiness, most people struggle to live virtuously.

This does not mean that we have to have our lives controlled in an authoritarian way by a central government. But it does mean that holding to healthy social norms and moral standards in a society is critically important. These are not fetters to individual liberty as Locke would have understood the meaning of liberty, but necessary supports for it.

And Locke's focus on an individual pursuit of liberty is also insufficient. It's not enough to hope that this individual pursuit of liberty will, of itself and without forethought, give rise to the necessary social conditions of life. The significance of a common good has to be explicitly recognised in its own right as a necessary component of individual well-being, and promoted as such.

Let's look at this realistically, taking family life as an example. Locke might have hoped that men and women would act according to reason and understand that their enduring happiness depended on rejecting the impulse toward promiscuity and choose instead to make a commitment toward a lifelong marital bond that would provide them with a secure base to enjoy the higher pleasures of paternal or maternal love, a lasting companionship into old age and so on.

How has that worked out? It turns out that reason struggles to overcome the innate impulse (that Locke never acknowledged) toward hypergamy. It turns out that not everyone shares the personality traits of conscientiousness or agreeableness that support successful pair bonding. It turns out that not all women will act prudently to leverage their assets of youthful beauty and fertility in a timely way that permits them to marry successfully. It turns out that some people will ignore the "save oneself for marriage instinct" and instead became jaded and incapable of deeper emotional attachments. And so on.

Individual reason alone does not uphold standards of virtue within a society. Our society is the living proof of this. The lessons of reason need to be reinforced and supported so that they become social norms and moral and cultural standards. The arts can play a role in this, so too can the churches, so too can schools and universities, as can churches. And, yes, governments have at least some role to play in this as well (think, for instance, of the harm done to family life by the way that family law is currently framed).

Another problem with Locke's concept of the individual pursuit of happiness is that, even understood as a pursuit of virtue, it is focused on the self alone. Here is one way of thinking about this. If I am concerned with the common good, then I will act in ways which uphold this common good. For instance, I will think it important that I deport myself in public in a way which upholds a higher standard. I will want to present myself in public at my best in order to contribute to the communal standard.

I suspect that is why there used to be a standard of common decency or why it was thought important to dress well when in a public place or why it was thought worse to bring our vices into public view than to keep them private. But we have increasingly lost this notion that what we bring of ourselves into the public square matters as part of a common good. People now not only fail to keep their vices private but will identify with them, and standards of dress are sometimes intended just as much to provoke a reaction or to assert individuality as they are to inspire people to a higher standard of the masculine or feminine.

Let's come back now to the libertarian idea that the founding fathers of the U.S. intended government to be morally neutral. I was looking recently at the symbolism of the Great Seal of the United States, which was adopted in 1782. The designer of the seal, Charles Thomson, described the symbolism as follows:

The colours of the pales are those used in the flag of the United States of America; White signifies purity and innocence, Red, hardiness & valor, and Blue, the colour of the Chief signifies vigilance, perseverance & justice.

The mindset here, by design and within the very seal of government, is a pursuit of virtue. The same point comes through very strongly in an article by Mathew Peterson titled "The American Founding was not Libertarian Liberalism". He gives many examples of how the founding fathers associated virtue with liberty and a loss of virtue with licence.

For example, James Madison said at the Virginia Ratifying Convention:

I go on this great republican principle, that the people will have virtue and intelligence to select men of virtue and wisdom. Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation. No theoretical checks—no form of government can render us secure. To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical idea.

So here then is the challenge for modern day libertarians. What is there in a libertarian politics to ensure that there is "virtue in the people"? Clearly, it doesn't happen of itself. It needs to be fostered in some way. So how? Libertarians not only reject the idea of government upholding moral standards as "fascist" or "theocratic," even worse they reject the notion of a common good as being "collectivist". So presumably they have to somehow connect the pursuit of an individual good to the creation of virtue in society. It hasn't worked this far. How do they think then it is going to work from here on in?

Libertarians and Conservatism Inc types seem to see it a zero-sum game. Anything that increases the common good must somehow reduce the individual good.

ReplyDeleteI'm also constantly amazed at the adolescent mindset of libertarians. They believe stuff that they should have grown out of by the time they left their teenage years behind.

And of course there's the maleness of libertarianism. It's an ideology that has zero appeal to women. Libertarians seem to be unable to comprehend why women (quite correctly) see libertarianism as something that cannot possibly benefit women.

These are valid points about the common good. But on their own they are just an naive of political reality as libertarians.

ReplyDeleteThe founders would not approve of 50% + government taxation, affirmative action, and government schools any more than they would full blown corporatism and a bureaucratic tyranny.

So how do you explicitly and with rigid boundaries set limits on the enforcement of the common good to prevent it from running away into communism in one of its many forms as most leftists and certainly the democrats in the US have accelerated endless in the past 40 years.

We have a bureaucratic tyranny for the 'common good'.

The danger is always that those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.

https://imgur.com/csXI6bL.png

Good question. Part of the answer, though, still comes back to the problem of excessive individualism. The leftists who seek a large bureaucratic state do so, in part, because they start out with the image of an abstract individual, who has no fixed nature, and therefore no part of his nature ties him to the loves, loyalties and duties of forms of community such as family or nation.

DeleteIf you are a traditionalist, and you do think of the individual as having these natural ties, and that freedom consists in fulfilling them rather than fleeing them, then you will envisage society in small-statist terms. You will not want the state usurping the masculine or feminine roles within the family, for instance. Nor will you want a large, bureaucratic, centralised state usurping the masculine role within a local polis - leaving men passive.

The leftists, on the other hand, see things in abstractly universal terms and combine this with a belief in perfectibility - and therefore with progress. You end up with a secular humanism in which we are "advancing" toward ever higher and more universal forms of social organisation - right up to the global state. You end up with the individual and the global state.

So, the brief answer to your question is that if we do not challenge the leftist view of man and his purposes, then yes the "common good" will lead us to a hollowed out society consisting of the individual and a very powerful UN.

But for many hundreds of years, pre-Rousseau & friends, this is not how the common good was understood. It was understood more in terms of man, a social creature, embedded within "natural" forms of community, and expressing the loves, loyalties and reciprocal duties that flowed from this.