Edwin Dyga has written an essay for the Observer & Review which explores the role of cinema in post-War Japan ("Cinema as Symptom and Vehicle of Social Re-engineering: A Post-War Japanese Study", Observer & Review Volume 2, Issue 1, Number 2).

Toward the end of the essay, in his concluding remarks, Dyga makes a connection between the assault on the traditional dynamic between men and women and the assault on traditional national identities. It's a connection I've made myself, but Dyga expresses it eloquently in his own way, and I thought it worth sharing.

Dyga begins the excerpt under discussion by noting "a tendency towards the mechanical view of Man and society".

This tendency was inaugurated in the early modern period of European history. Basil Willey begins his book on The Seventeenth Century World Background by quoting part of a work by Fontenelle, published in 1686. Fontenelle has a philosopher conversing with a countess as follows:

"I perceive", said the Countess, "Philosophy is now become very Mechanical". "So Mechanical", said I, "that I fear we shall be quickly asham'd of it"; they will have the World to be in great, what a watch is in little; which is very regular, & depends only upon the just disposing of the several parts of the movement. But pray tell me, Madam, had you not formerly a more sublime Idea of the Universe?"

This was a great shift in world picture from what had gone before. Dyga's essay notes an "aesthetics of dehumanised artificiality" within Japanese cinema as a modern development of this mechanical view. He argues that this is "acutely hostile to the idea that Man's sense of self is shaped by his place within natural hierarchies derived from a transcendental understanding of the human condition."

This is well observed. One way of putting this perhaps is that the new cosmology (of a mechanical universe) does not allow for an older anthropology (in which Man's sense of self is shaped by his place within natural hierarchies).

And here is the key point. Once you set man outside of these natural hierarchies derived from a transcendental understanding, what then is there to ground a sense of who man is and what his telos - his ends or purposes - in life might be?

For Dyga, the mechanical picture of the world "favours an understanding of the individual as an essentially self-defined entity, and therefore susceptible to recreation at will. No inherited essence means no particularity".

The rejection of inherited essence is prevalent in modern thought. Here, for instance, is Judith Butler putting forward the idea that there are no essences, and that therefore gender is just a performance and a construct:

... gender is a performance ... Because there is neither an “essence” that gender expresses or externalizes nor an objective ideal to which gender aspires; because gender is not a fact, the various acts of gender create the idea of gender, and without those acts, there would be no gender at all. Gender is, thus, a construction...

If there is no inherited essence, then, argues Dyga, there is no particularity. This is a thought that can be drawn out, and I will do so later in this post. But, as a brief observation, it is true. In a machine like cosmos there are only parts arranged in certain ways to give certain effects - there are not "qualities" that are embedded in reality, that carry inherent meaning and that make groups of things distinctly what they are.

|

| Judith Butler |

Dyga goes on to explain that,

The resulting decomposition of the national polity through the erasure of memory and the distortion or the pathologisation of history is no accident, because it is here that inherited essences and particularity is rooted on a macro level.

In other words, if we are thought to lack inherited essences at the level of who we are as individuals, then these will also be rejected at a higher social level. This will take the form of wanting to erase memory and distort history (think of toppling of statues, or hostility to founders, or strange casting decisions in historical dramas).

I would add to this that those with the most modernist of minds are often simply blind to the very possibility of traditional national cultures. If someone says to them "I wish to defend my national culture", their answer is often a perplexed "But what is that culture? Does it exist?" I have even heard an Austrian being interviewed in the streets of Vienna, immersed in his own national culture, say "But what is Austrian culture anyway?". This is similar to Judith Butler proclaiming that "gender is not a fact" - despite the observable differences between the sexes being obvious to those with eyes to see.

Dyga finishes the excerpt by writing:

There is a direct interrelationship between the destruction of the individual and his ethne, and the process is catalysed by the intentional rejection of the inherited patrimony through the process of cultural destruction; the assault on the traditional sexual dynamic further enhances that process. The national and sexual 'questions' are therefore profoundly interrelated; they cannot be approached separately...

It makes sense that if the individual is destroyed by the modern world picture, then so too will be his larger community, his ethne.

Some thoughts on how this came to be

I'd like to use part of Dyga's excerpt as a platform to branch off into some thoughts of my own. The relevant quote is the one in which Dyga argues that a machine like understanding of reality,

favours an understanding of the individual as an essentially self-defined entity, and therefore susceptible to recreation at will. No inherited essence means no particularity.

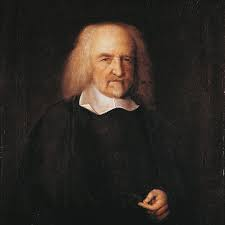

The undermining of essences goes back a long way, perhaps even to the nominalists of the medieval period. But it seems to me that a good starting point is Thomas Hobbes in the seventeenth century.

|

| Thomas Hobbes |

Hobbes rejected the notion of essences and also what were called "final causes" (the idea that things have a purpose). Instead he held that beings were subject to "efficient causes" (the sources of motion and rest).

For Hobbes, the focus is on the desires and aversions that move us toward some object or repel us from it. The things we desire we consider good, those that repel us as bad.

We are acted upon by external causes in our desires and aversions, and so what we desire is determined at an individual level (so that individuals will desire different things). In this sense we have no free will.

But Hobbes is a compatibilist. This means that he believes we have a certain kind of free will, namely to act without impediment to realise the desires that are determined for us. If we can do this then our will is free in the sense of being unimpeded.

So here is the issue. Hobbes's way of dealing with a mechanical cosmos does not initially seem to point to the idea of people being self-defining entities susceptible to recreation at will. After all, who they are is determined by the way the environment acts upon them.

However, in the Hobbesian view we each have our own unique desires that constitute who we are and the aim is for there to be nothing to hinder us in the pursuit of these desires (except when the strong arm of the state is necessary to preserve our life and our property from others).

So even though our desires do not come from our own free will, you still end up with an individual who believes "this is what I desire to be, so I should be free to be this without impediment". These desires are conceived to be uniquely determined, so this undermines the idea that they might be derived from distinct and particular qualities that we share with others (essences).

The Hobbesian view runs against certain aspects of modern science, such as the idea of genetic coding or even of evolutionary adaptation. For instance, humans are dimorphic with clear distinctions between the sexes that are related to different roles throughout the long human prehistory. This dimorphism is biologically coded in relation to chromosomes, hormones, brain structure and so on.

Those committed to modernist ideas about every individual being uniquely ordered toward their own desires and, in this sense, self-defining, will often downplay this biological coding. They will argue that the only relevant biological differences between the sexes are "what is between the legs" or they will argue fiercely against evidence of brain differences between the sexes or they might claim that the coding is no longer relevant and can be overridden (or even rewritten).

To give some idea of how influential the kind of view held by Hobbes was in the Anglo tradition, consider the case of Victoria Woodhull, a prominent American feminist of the 1870s. As you might expect, she wanted to abolish the distinctions between peoples and between the sexes, arguing that women should be "trained like men" and that there should be a merging of the races to achieve a unitary world government. Her metaphysics sound very similar to those of Hobbes:

But what does freedom mean? "As free as the winds" is a common expression. But if we stop to inquire what that freedom is, we find that air in motion is under the most complete subjection to different temperatures in different localities, and that these differences arise from conditions entirely independent of the air...Therefore the freedom of the wind is the freedom to obey commands imposed by conditions to which it is by nature related...But neither the air or the water of one locality obeys the commands which come from the conditions surrounding another locality.

Now, individual freedom...means the same thing...It means freedom to obey the natural condition of the individual, modified only by the various external forces....which induce action in the individual. What that action will be, must be determined solely by the individual and the operating causes, and in no two cases can they be precisely alike...Now, is it not plain that freedom means that individuals...are subject only to the laws of their own being.

The Western mind, for a time at least, was also influenced by the German idealist tradition. During the Romantic era, there was a backlash against the machine like understanding of the cosmos. Writing in the late 1700s the poet Novalis complained that,

Nature has been reduced to a monotonous machine, the eternally creative music of the universe into the monotonous clatter of a gigantic millwheel.

Some of the German idealist philosophers reacted against the determinism implied by this world picture (of no free will) by asserting the independence of the absolute "I". But they did so in catastrophic ways. Against the idea that the phenomenal world of existence determined who we are, they asserted that the absolute "I" might posit itself against this world. There was now a kind of hostile relationship between the given world of being and the free self, which later developed into nihilism. Here is a description of a university lecture by the German philosopher Johann Fichte:

As Fichte stood at the podium in Jena, he imbued the self with the new power of self-determination. The Ich posits itself and it is therefore free. It is the agent of everything. Anything that might constrain or limit its freedom - anything in the non-Ich - is in fact brought into existence by the Ich.

Fichte saw himself as a liberator:

My system is the first system of freedom: just as the French nation is tearing man free from his external chains, so my system tears him free from the chains of things-in-themselves, the chains of external influences.

But this liberated will now stood against phenomenal reality:

My will alone...shall float audaciously and coldly over the wreckage of the universe.

So in reacting against the machine like world picture, these philosophers doubled down on the idea of freedom being an act of self-determining will. Instead of re-picturing external reality, it was defeated to the point of wreckage by the absolute "I".